M3GAN 2.0

Directing: B-

Acting: B

Writing: C

Cinematography: B+

Editing: B-

Special Effects: B

I go to the movie so often, I often have to sit through trailers to the same movie so many times that, even if I am interested in the movie, I get deeply sick of the trailer. MEGAN 2.0 was a prime example of this, and it also means I committed a great deal of that trailer to memory—against my will. There’s M3GAN breaking through a giant doll box to strangle a man. There’s M3GAN saying to rival robot AMELIA (“Autonomous Military Engagement Logistics and Infiltration Android”), “I’ll make you a deal. You can kill Gemma, but don’t touch Cady,” before an exasperated Gemma (Allison Williams) snaps, “M3gan!” (She pronounces the 3 as an “e.”) And best of all, there’s the obviously-gay stan in a blonde wig who says, “I don’t care if she did kill four people. She is a smoking’ hot warrior princess!”

Except: none of these slips from the trailer are actually in the theatrically released cut of the movie. This is fairly common, as editing of the full film typically isn’t done when trailers are cut. But it seems particularly egregious here—some of the most fun stuff used to sell us on the movie isn’t even in the movie. Are we supposed to wait around for a “director’s cut,” or what? Of this?

The original M3GAN (2022) got surprisingly good reviews. I thought it was fine. To be fair, it seems to work better as a re-watch: I watched it again to refresh my memory before going to see this sequel, and I think I enjoyed it more the second time around. I still stand by the solid B I gave it. M3GAN 2.0 isn’t faring quite as well with critics. It is objectively less-good than its predecessor, but let’s be real: not by a huge margin. There is some bonkers-ridiculous shit that happens in this movie (in what universe would an obvious home invasion turn out to be the FBI coming in with a search warrant? Well—this one!), and yet: I still found myself having a pretty good time in spite of it all.

Perhaps the most obvious thing about M3GAN 2.0 is its existence as a reaction to an original film that found far greater success than anyone expected, thanks to a sneakily campy tone that did not fully reveal itself until the second half of the movie. Now, not only is most of the principal cast returning (including Violet McGraw as Cady, now three years older), but so are the writers (Aleka Cooper and James Wan) and the director, Gerard Johnstone. The only difference there is that this time around Johnstone is also getting a writer credit. And what every one of these people are trying to do is transparently to catch lightning in a bottle. This predictably proves impossible, mostly because it can no longer be sly about its subtle camp—and yet, it does get closer than you might expect.

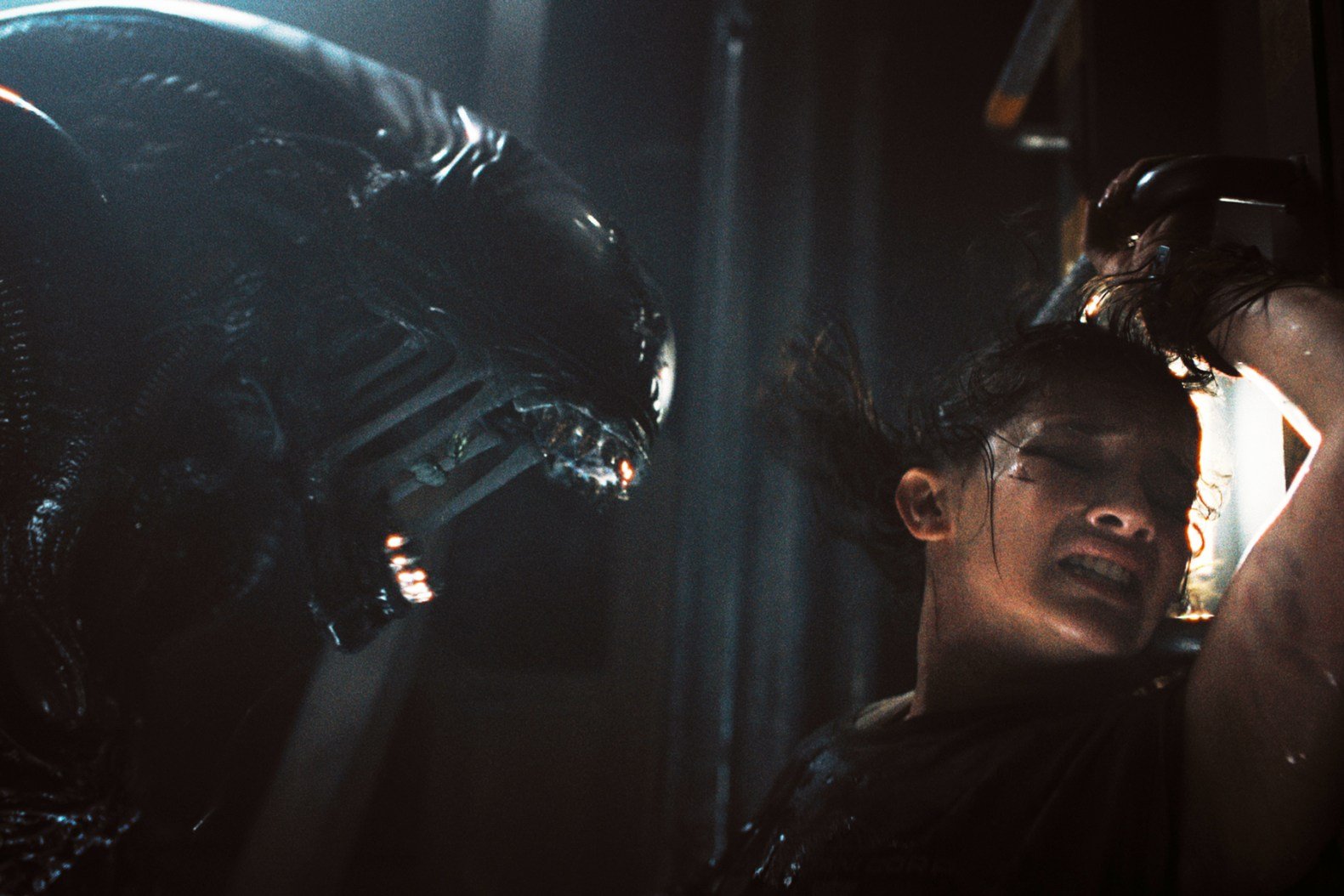

They also go very obviously for a Terminator 2 version of M3GAN, where the character who was the lethal villain in the original film is brought back to become the hero, and fight against a more advanced villain. To 2.0’s credit, M3GAN the character remains pretty threatening and sinister well after getting re-introduced into this new story. The greater threat now is AMELIA, this one an android played fully by a real human (Ivanna Sakhno, perfection the art of not-blinking). It also takes a page from the Alien franchise, dialing down the horror from the original film and leaning into action.

You may be sensing a theme here, in that there aren’t really any original ideas to be found. There’s still joy in the project, and that is still to be found in the tone: M3GAN’s bitchy attitude; some of her tone deaf decisions (there’s a scene of her singing a song to Gemma at the wrong moment and I got a kick out of it); even the multiple choices clearly mirroring similar moments in the first film. Some of it lands better than others; when we get a M3GAN dance at an unexpected moment in this movie, it doesn’t work anywhere near as it did the first time around precisely because now we’re expecting it, waiting for it to happen.

Part of what made M3GAN work as well as it did—to the extent that it did work—was the character’s very size: she’s small for a girl, big for a doll, but still quite obviously a doll. This time, when Gemma redesigns her, M3GAN says “Make me taller.” This makes her a bit less effective as an amusingly creepy doll, but at least she remains markedly shorter than any of the adult humans around.

No one expects a movie like this to be plausible, but some of this stuff threatens suspension of disbelief, even by M3GAN standards. If she can construct an entire basement lair complete with wall screens and furnishings, why in the world would she need Gemma and her colleagues to help construct her an upgraded body? But whatever, when she and AMELIA are fighting, it’s fun—especially AMELIA’s cleverly gruesome kills. The action is actually used more sparingly than it needs to be, but the restraint on that front actually helps it work.

I suppose there can also be too much restraint, though. The original film was a perfect length at 102 minutes. M3GAN 2.0 is a solid two hours, which, for a movie like this, is . . . not perfect. There’s actually more to enjoy than you might expect in this film, but the flip side is how it can give you too much of a good thing. The marketers of this movie clearly attempted to capitalize on a character that instantly became a camp icon, but such things never land exactly as desired when you have to work so hard at it.

It works well enough, though. M3GAN 2.0 is mostly ridiculous and stupid, and these are things the movie knows about itself, which made it easier for me to just enjoy it for what it is, which is postmodern horror with a lot of deliberately weird humor. Even as it turned out definitively less good than the original, I kind of hope they make a M3GAN 3.0. And you never know, the next one could be better! We just won’t talk about the inevitable downsides of planned obsolescence.

You’re gonna let me finish no matter how long it takes!

Overall: B-