COMPARTMENT NO. 6

Directing: B

Acting: B+

Writing: B

Cinematography: B+

Editing: B

Compartment No. 6 is a relatively impressive film on a technical level, if you pull out of the story long enough to think about it, anyway. This feels a little like a backhanded compliment, I admit, since it does mean that, while I generally found the story compelling. I did find time to wonder how successful they were at maintaining continuity. This film is mostly set on a train from Moscow to the far-northwest Russian city of Murmansk, not far from Scandinavia, and it is largely shot legitimately on moving trains.

I’d be interested to know how they accomplished this, but can only assume many scenes were shot far from where the train the story was actually supposed to be running. And, indeed, the cinematography, all with hand-held cameras, is one of the more noticeably accomplished aspects of this film, the camera following characters along incredibly tight train car corridors, to and from a rather small compartment space.

This film, perhaps, also falls victim to world events, in respect to the country in which it is set. Compartment No. 6 is a Finnish film, with a Finnish director (Juho Kuosmanen) and a Finnish actor (Seidi Haarla) playing the Finnish protagonist, named Laura. But, Laura is the only Finnish character in this film; all the others are Russian, as she’s staying in Russia, learning the language, and going on this train trip that had originally been planned with the older Moscow woman she sublets from (and sleeps with) but who had to cancel due to work.

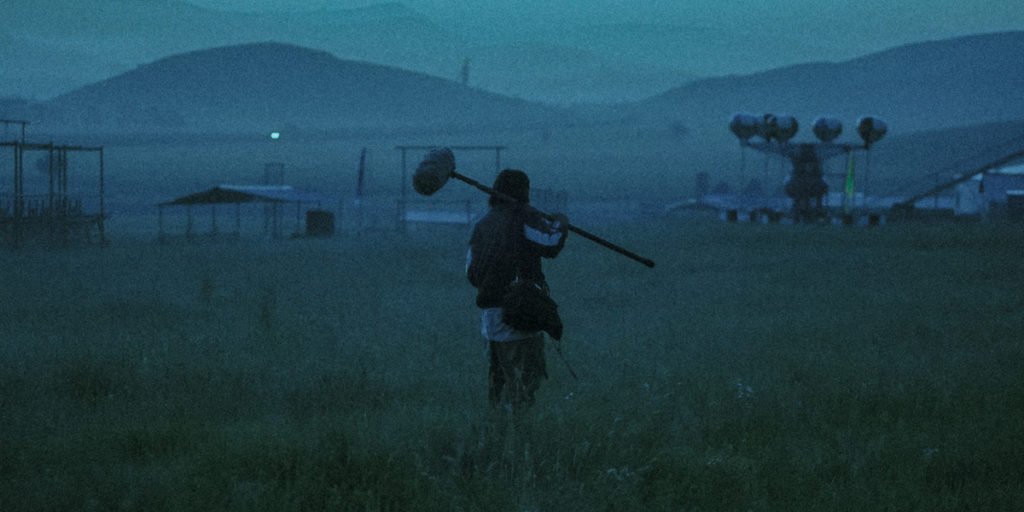

Laura has gone ahead and taken the trip on her own anyway, to see the Kanozero Petroglyphs. The story here isn’t so much about that; it’s just a destination for the train ride that serves as the setting for most of the story. What we are to be more interested in, is her tentative but slowly developing relationship with Ljoha (Yuriy Borisov), her randomly assigned compartment mate.

When Laura first encounters Ljoha in their compartment, he is drunk. A little on the nose for the Russian character, perhaps. But, Borisov imbues him with incredible nuance, slowly revealing the unique nature of his emotional repression.

That said, not a whole lot happens in this movie, really. It’s just a very talky drama, set on a train, with a fair number of very quiet moments. It recalls Richard Linklater, just less brainy (and actually less talky). If you’re looking for any kind of excitement, you won’t find it here, You won’t even find any romantic fireworks, although there is a bit of a near miss with romance. Personally, I kind of liked this aspect of it, as it’s nice to see a movie about a man and a woman that doesn’t focus at all on sex. There is a kissing scene, but then Ljoha retreats from it, seemingly almost involuntarily.

It’s nice that none of the main characters in this movie is a villain, at least. The closest we get to supporting characters is the woman train conductor, and the elderly lady Ljoha brings Laura along to visit during an overnight stay in St. Petersburg. Oh, and the other Finnish passenger who shares the compartment for a brief period. He spends a little too much time softly singing along to his acoustic guitar.

Compartment No. 6 is credited as being “inspired by”—as opposed to based on—a novel by the same name by Finnish writer Rosa Liksom. It was first published in 2011, so both the novel and this movie were made before all this Ukraine bullshit with Russia—one has to wonder whether this movie could even be made were it in production in 2022. Instead, the movie was shot in early 2020, some locations forced to change due to the emerging pandemic. Do current events affect public appetite for even partly Russian stories, I wonder? It didn’t affect mine; Russian people are still people, and this story can exist irrespective of what horrid things the Russian president is doing. Beyond that, there’s not much definitively memorable about it, but Compartment No. 6 has is charms.

She begrudgingly opens up to his friendly overtures, just like I did with this movie.

Overall: B