Below are the ten most satisfying and memorable films I saw in 2023:

10. Barbie A-

10. Barbie A-

Remember America Ferrara's speech everyone raved about online? I recently heard someone characterize it as "it sounds like AI," and you know what? Fair. Also: beside the point.

Barbie's inclusion in my top ten for the year as connected to, but about far more than it being the biggest movie of the year. There's something to be said for a movie

like this one becoming the biggest movie of the year, with its seemingly cliche platitudes which nonetheless got mainstream exposure like never before. A cliché doesn't sound like a cliché when you're hearing it for the first time, and both Margot Robbie and Ryan Gosling give genuinely award-worthy performances. Greta Gerwig being the director and co-writer of this expertly constructed film is the sole reason I had any interest in it to begin with, and not only did she not disappoint, she massively exceeded expectations. Women can make giant blockbusters too! Women are just as capable of harnessing late-stage capitalism!

What I said then:

A different director could have made a film version of Barbie

that was every bit as fun, and maybe even worth seeing, but only Greta Gerwig, with the help of her expertly curated ensemble cast, could so successfully pack the movie with subtext. Even better, viewers with no interest in the subtext can just as easily enjoy the movie on a surface level—this doesn’t have to be an intellectual pursuit, or something you have to analyze or deconstruct. Gerwig’s genius is in how she makes that possible without making it necessary.

9. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse A-

9. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse A-

How do I account for my inclusion of

Across the Spider-Verse here, when its predecessor,

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, which I also gave an A-minus, did

not make it onto my top 10 in 2018? Both films are similarly exhilarating viewing experiences, after all. All I can say, I suppose, is that I saw more films in 2018 that had a deeper impact on me. Furthermore, I would argue, the fact that

Across the Spider-Verse matches the previous film's quality in every way, and in some ways perhaps even surpasses it, is an even greater accomplishment. Now, I benefited from the prior knowledge, going in, that this was to be the first of a story split in two parts, so I was not incensed, as some were, by its cliffhanger ending, which I was fully anticipating. And everything up to that point is a mesmerizing kaleidoscope of distinct artistic styles associated with different characters, each of which is given far more dimension than in any average live-action superhero film.

Across the Spider-Verse is as often hilarious as it is moving, layered with both thematic and visual meaning. It has far more to offer than can be taken from just one viewing.

What I said then:

It can be hard to trust any assertion that a movie has everything you could possibly want and more, but in this case, you can take that to the bank. The movie’s producers almost certainly will. This movie is a truly amazing specimen of cinematic craft.

8. BlackBerry A-

8. BlackBerry A-

Maybe the biggest cinematic surprise of the first half of 2023,

BlackBerry may not be quite the instant classic that

The Social Network had been, but it's the closest we've come in a long, long time. This movie, about the minds behind the staggering success of the BlackBerry mobile device and its rapid fall in the face of Apple's iPhone, has a propulsive energy unlike any other film this year.

BlackBerry deserved far more attention than the little it comparatively got—it barely fell short of $2 million worldwide, on an otherwise tiny budget of $5 million—though it later aired as a slightly expanded miniseries on AMC. In any case, it was one of the more thrilling experiences I had in a cinema this year.

What I said then:

It’s not the story, it’s how it’s told. It’s good to remember that if you hear that there is a movie about the rise and fall of the first mass-market mobile device, the BlackBerry. Because this film, directed, co-written and co-starring Matt Johnson, is stunningly propulsive, edge-of-your-seat stuff.

7. Past Lives A-

7. Past Lives A-

There's something about the way this film is constructed, it's just . . . achingly beautiful. It's also very sad, a story of missed opportunities between a boy and a girl who start of as best friends in Korea, and then the girl, over the years, moves with her family to Canada and then to the U.S. It's a deceptively simple premise, with deeply affecting, if subtle, layers of emotion. In the end, there's a love triangle of sorts, except not quite exactly, a scenario when these two people who have longed for each other all their lives are faced with a romantic conundrum.

Past Lives is a quite film with a hell of a lot to say, culminating in a "What would you do?" scenario for the ages. This is the kind of movie that deserves to be remembered and savored for generations.

What I said then: Past Lives

is a unique experience, in that its emotional resonance takes some time to percolate. I nearly started crying thinking about it on my way home after the movie ended, and I still can’t really say why, except that the movie permeated my soul, and it took some time for me to focus on anything else, rather than continuing to think about this deeply affecting love story.

6. May December A-

6. May December A-

What would we do without the mind of Todd Haynes, which isn't so much fucked up as it is concerned with deeply nuanced depictions of fucked up people? This has never been more the case than with

May December, a film so directly inspired by the Mary Kay Letourneau story that it blurs the line between fact and fiction. Except, it is also a compelling thought exercise: Latourneau and her husband divorced after 14 years of marriage, but this film asks the question: what if they were still married, twenty years after the affair between an older woman (Julianne Moore) and a younger man (a standout Charles Melton)? And for good measure, let's throw in an actress (Natalie Portman), visiting the family, taking "research" to dubious lengths as she prepares to star in a TV movie based on their story. The dynamic between Moore and Portman is especially fascinating, as is the dynamic between Melton's character and his children, who are unnaturally close to him in age. Of all the movies I saw this year, this one arguably has the most to talk about—and boy, is it fun to talk about.

What I said then:

There’s a subtle narrative thread here, touching on the salacious fascination we have with sensationalized stories like this. Natalie Portman is absolutely incredible in this role, as a woman overstaying her welcome as she “researches” the role, taking the task to new and dangerous places, fucking with the stability of people already existing in precarious emotional spaces. Elizabeth engages in her own sort of grooming, gaining the trust of people she is ultimately just using for the purpose of serving her onscren performance.

5. Close A

5. Close A

Close has an unfortunate taint to it, in that it was directed by Lukas Dhont, who previously made a film about a trans girl that was rightly critically reviled for its irresponsible depictions. If there is any possibility for redemption, though, then

Close is it, a vividly realized example of a filmmaker taking on a subject that allows him actually to write what he knows. This is about adolescent boys, with a deep connection, both emotional and physical in ways that they don't register consciously—and then, in ways they are too young to understand, an insidious bit of homophobia splits their pure and innocent connection in two. Your heart aches for these boys, because you understand what they don't have the ability to contextualize.

What I said then:

One of many things Dhont deftly handles in Close

is the way adolescents experience feelings that have no tools to articulate. Something is definitely happening between these boys, but neither of them knows or understands exactly what. We, as observers in the audience, are the ones who understand: Léo is afraid of being misjudged by his peers; Rémi is deeply saddened and doesn’t know for certain why. It’s heartbreaking to watch, and will make you recall your own cherished childhood friendships that fell apart without explanation or warning.

4. The Holdovers A

4. The Holdovers A

If I just went by how the movies made me feel, I might very well have ranked

The Holdovers at #1—this was, by a mile, the most heartwarming film I saw this year. The premise isn't even particularly profound: a loner teacher at a private school (a reliably fantastic Paul Giamatti) gets stuck with chaperoning several students unable to go home for the holidays, and first butts heads with and then forms a bond with a similarly contemptuous student (Dominic Sessa). But there's something about the way director Alexander Payne and writer David Hemingson present this story, in a film specifically stylized to feel not just like it's set in, but as though you're actually watching it in the early 1970s, that just works. It may sound conceptually pretentious, but there is such sincerity in the performances and presentation that you leave the theater feeling thoroughly uplifted, for both the characters and for your own experience at the movies.

What I said then:

It’s difficult to put into words how wonderful I found The Holdovers

. It filled my heart. I tried to think of other descriptors that could work. There’s an element of sweetness, I suppose, but that’s not really what the movie is. Maybe “wholesome” is the right word. Yes, I think that’s it: many “feel-good” movies of the 21st century are self-consciously bawdy with a “wholesome” subtext that just rings false. The Holdovers is the kind of movie that is never bawdy although it can be slightly vulgar when it wants to be, and it gets its tone of wholesomeness exactly right.

3. Anatomy of a Fall A

3. Anatomy of a Fall A

A stunning accomplishment of cinematic craft,

Anatomy of a Fall just begs for analysis—in all the best ways. Don't let the two-and-a-half-hour run time deter you: this film is riveting from start to finish, even if some of the earlier scenes seem at first to lack purpose, "at first" being the operative phrase. You'll want to pay close attention, because every moment ultimately proves to be important, making this one of the most compelling crime dramas to come along in many years. To say it's less a "whodunnit" than a "did she do it?" very much undersells the skill and artistry at play in this film, particularly when it comes to interpersonal dynamics between a married couple, their young, blind son, and even their dog. The fact that the wife and mother is German, the husband and father is French, and neither has learned the other's language well enough so they speak in English at home, only enriches the material, as how communication might get lost in translation becomes a key detail, particularly in French courtroom scenes in the second half of the film.

Anatomy of a Fall is an intricate family drama as much as it is a murder mystery, and it starts strong and only gets better as it goes along.

What I said then:

In Anatomy of a Fall

, every detail matters. Sandra Hüller’s performance in particular is stellar in its ambiguity, easily gaining empathy but with an undercurrent of doubt, obstinately stoked by the prosecuting attorney, and indeed the inconclusive evidence itself. When all this ambiguity is the result of such deliberate intention, the result is a masterful achievement.

2. A Thousand and One A

2. A Thousand and One A

For a solid eight months, I was telling everyone that

A Thousand and One was the best movie I've seen this year. The title references an apartment number, in New York City between 1994 and 2005, during which a young mother (Teyana Taylor) struggles to raise a boy she illegally pulled out of the foster care system, shortly after she was released from prison. The technicality of whether she kidnapped Terry (played in different segments by three different young actors, each distinct and equally excellent) is incidental to this story, which focuses far more on the challenges of raising a young Black man, often subtly contextualized in the local city politics—and, in particular, the NYPD policies and practices—of the time. This is a period piece of recent history, an intimate portrait that still serves as a reflection of how America's flagship city has evolved, and a story with a dramatic turn at the end that may spark some debate. I was good with it, because I was so deeply impressed with every facet of this movie's production.

What I said then:

Rarely does such a vividly drawn portrait so effectively occupy the gray areas of life and history. In this case, writer-director A.V. Rockwell proves to be such a talent with a first feature film that I can’t even say she has potential. She’s already realized it. I can only say that I already breathlessly await whatever she makes next, and if she doesn’t have a vastly accomplished career ahead of her, we will have all been criminally deprived.

1. Maestro A

1. Maestro A

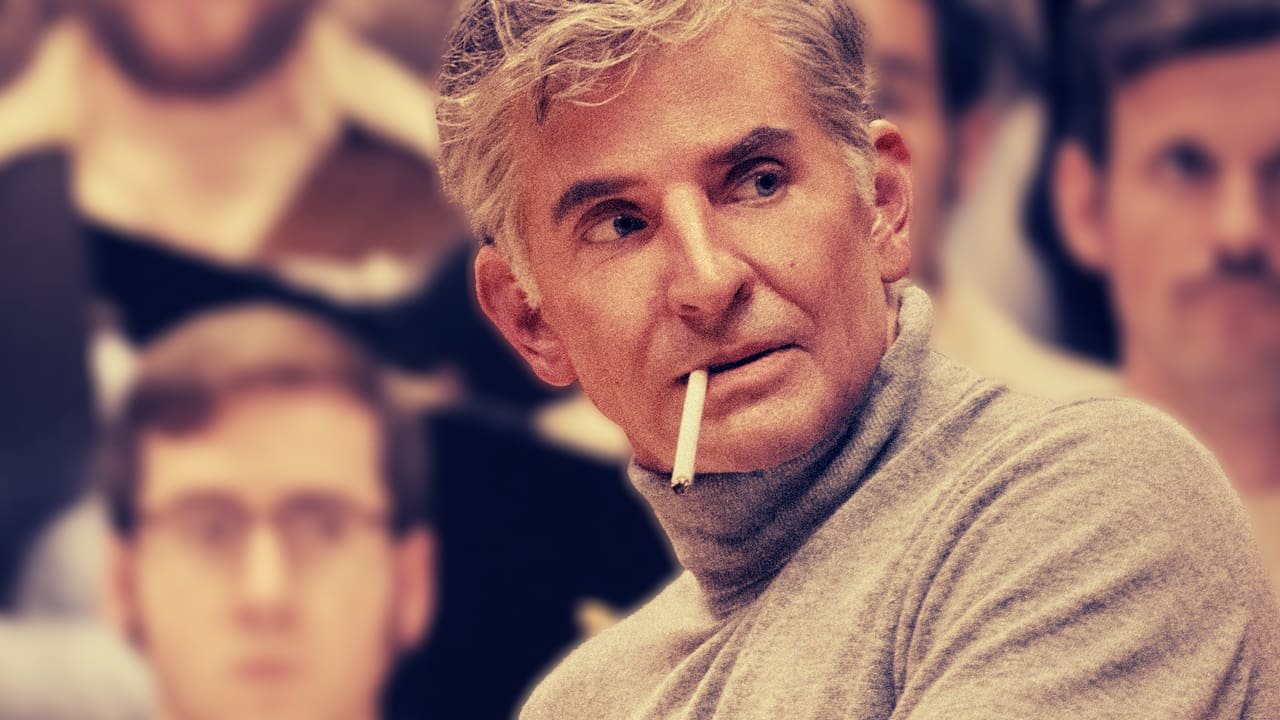

Simply put,

Maestro knocked my socks off. My only regret is that this was one of the Netflix-produced films with such a short theatrical window that I had no choice but to watch it at home—and yet, I immediately watched it a second time the very next day, a rare thing indeed. The way I see it, the people criticizing this film's comparative lack of focus on Leonard Bernstein's career as a conductor and composer are missing the point—Bradley Cooper's intent is to explore how that level of acclaim and success affects a person's relationships, especially his marriage. The fact that Bernstein was also queer, a very important aspect of the story as told here, only enriches this examination—and Cooper is transformative, transfixing, and an astonishing revelation as Bernstein. Some might find my reaction to Cooper's accomplishments here, both as actor and as director, to be unjustifiably hyperbolic, but I stand by it, especially after seeing the film a second time. How he can turn in a performance like this, while also directing the film, defies the imagination. And Carey Mulligan is every bit as impressive—if far less literally transformed—as Felicia, Leonard's genuinely beloved but also understandably beleaguered wife.

What I said then:

Honestly I’m not sure I could even count the ways I loved the experience of watching Maestro

. I expected to like it, and to say it exceeded my expectations would be an understatement. I’m gushing so much over it now, I fear it may make readers set their own expectations either impossibly high, or with an unfair amount of skepticism. I can only speak my truth: I loved this film.

Five Worst -- or the worst of those I saw

5. Babylon C

5. Babylon C

I know, I know—a solid C grade is merely average, as opposed to

bad. Well? If you want me to review movies I already know will be terrible, you can pay me to do it! Any takers? As it is, my "five worst" winds up just being the five films I most

misjudged whether I would like them. In the case of

Babylon, this film tested my patience from its very release date, at least locally: technically a 2022 film, I could not see it locally until January. It was not worth the wait, and then I had to wait nearly an entire year to complain to you about it! The POV elephant shit and the golden shower, both within the first ten minutes, are the tip of the iceberg in this wildly unnecessary, wildly excessive, 189-minute movie, about the wild excesses of the last days of the silent movie era. Haven't we covered this terrain already?

What I said then:

I went to BABYLON really wanting to love it. Damien Chazelle has made films I consider to be truly great. This one, though, feels like the last, desperate attempt of an auteur throwing all of his unused ideas into a movie, as though terrified no one will ever allow him to make another one. The sad irony is that none of those ideas were particularly original.

4. Saint Omer C

4. Saint Omer C

If the massive critical acclaim

Saint Omer received is any indication, it's entirely possible that this is an example of a movie where "Matthew just doesn't get it." I'm not above admitting that. All I can say is, this movie, about a novelist attending the trial of a woman who abandoned her baby on a beach to drown to death at high tide, bored me senseless. If you really want to see a great film that spends an inordinate amount of time in a French courtroom, see

Anatomy of a Fall. That one, at least, spends a sensible amount of time outside the courtroom.

What I said then:

I can’t help but wonder if I am being unfair to this film—a feeling I have only because of its otherwise universal critical acclaim—but I can only be honest about my personal experience with it. When the film ended, after what felt like an eternity of tedium, I felt sweet relief.

3. The Origin of Evil C

3. The Origin of Evil C

Another one with good acting . . . and that's the only particularly good thing about it. With direction and writing that's at the high end of mediocre, and cinematography and editing that skirt the edges of bad,

The Origin of Evil is a French family drama with intricate plotting that gets less interesting with each successive turn. It's like

Knives Out but without the fun.

What I said then:

Here’s something I’ve never said about a movie before: The Origin of Evil

might just be too French or its own good. Full of unlikably arrogant people, with an inflated sense of self. Not all of the French are like that, I’m sure; these are stereotypes. But this movie isn’t doing them any favors. ... It gets progressively weirder, in less compelling ways.

2. The Flash C

2. The Flash C

Possibly the greatest waste of potential (and resources) in cinema this year,

The Flash actually had a lot going for it, with Michael Keaten actually returning as an aged Batman—a good portion of his presence in the film actually being pretty fun. But, why he gets grafted onto this garbage dump of bad CGI action set pieces is a mystery. And all of that's not even to mention how star Exra Miller evidently turned out to be a massive creep. That aside, if this movie could have just been the second act, expanded into its own feature length film, I might have actually enjoyed it on the whole. Instead, the first and third acts are just witless, poorly rendered messes telling a story I couldn't be bothered to care about.

What I said then:

The bottom line is, The Flash

is a shit sandwich with a moderately tasty center, except what’s the point of a tasty center in a shit sandwich? I suppose we could call the two Ezra Millers in it the buns. There are some nice shots of their butt in that suit, for what it’s worth. And for the record I am separating the art from the buttocks.

1. Renfield C-

1. Renfield C-

I actually had relatively high hopes for

Renfield, the movie with Nicholas Hoult as the title character, indefinite servant to Dracula, played by Nicolas Cage, who famously loves to work, apparently so much that he can act in his sleep. Which he might as well have been doing here, a bit of an irony for a film that shifts into manic-mode within the first five minutes and never lets up, relying solely on excessive gore as its "humor" and never managing to be funny enough—or even fun enough—to live up to its premise. Someone should remake this movie about a "familiar" coming to grips with his codependent relationship with a vampire, but with writers who have talent.

What I said then:

I’m sure some people will be entertained by Renfield

. Those people have no standards and no taste. Okay, maybe that’s a little harsh. A more generous read on this movie would be that it’s an homage to mediocrity. The run time is merely 93 minutes and I was more than ready for it to be over after thirty. Why couldn’t they hire whoever cut the trailer to edit the movie?

Complete 2023 film review log:

1. 1/5

MEGAN B

2. 1/6

Women Talking B+

3. 1/7

BABYLON C

4. 1/14

Saint Omer C

5. 1/16

The Pale Blue Eye B *

6. 1/17

Plane B

7. 1/26

Living B+ *

8. 1/31

Infinity Pool C

9. 2/2

Knock at the Cabin B-

10. 2/9

Exposure B+

11. 2/10

Close A

12. 2/12

Titanic 25th Anniversary (3D)

B **

13. 2/14

80 for Brady B-

14. 2/15

Godland B-

15. 3/9

Cocaine Bear B+

16. 3/13

Emily B

17. 3/29

John Wick: Chapter 4 B

18. 3/30

Linoleum B+

19. 4/6

A Thousand and One A

20. 4/11

Air B

21. 4/12

How to Blow Up a Pipleline B+

22. 4/17

Renfield C-

23. 5/2

Polite Society B

24. 5/4

Are You There, God? It's Me, Margaret. A-

25. 5/6

Beau Is Afraid B-

26. 5/9

Joyland A-

27. 5/12

The Mattachine Family B+ ***

28. 5/14

And the King Said, What a Fantastic Machine B ***

29. 5/15

BlackBerry A-

30. 5/18

Hidden Master: The Legacy of George Platt Lynes A- ***

31. 5/19

Being Mary Tyler Moore B ***

32. 5/20

Theater Camp B+ ***

33. 5/23

Filip B+ *** / *

34. 5/24

Monica B+

35. 5/27

You Hurt My Feelings B+

36. 5/29

The Eight Mountains B+

37. 6/2

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse A-

38. 6/5

Sanctuary C+

39. 6/11

You Hurt My Feelings B+ (

2nd viewing)

40. 6/16

The Flash C

41. 6/22

Asteroid City B+

42. 6/26

Past Lives A-

43. 6/30

Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny B

44. 7/2

Every Body A-

45. 7/3

No Hard Feelings B+

46. 7/9

The Lesson B

47. 7/10

Joy Ride B

48. 7/11

Biosphere C+

49. 7/14

Mission: Impossible - Dead Reckoning Part One B

50. 7/22

Oppenheimer B+

51. 7/23

Barbie A-

52. 7/25

Mission: Impossible - Dead Reckoning Part One B (

2nd viewing)

53. 8/12

Barbie A- (

2nd viewing)

54. 8/14

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem B

55. 8/18

The Unknown Country B+

56. 8/27

Strays B

57. 9/3

Bottoms B+

58. 9/8

Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe B+

59. 9/18

Fremont B

60. 9/25

Mutt B

61. 9/28

The Origin of Evil C+

62. 9/29

Stop Making Sense 40th Anniversary Rerelease A-

63. 10/1

The Creator B

64. 10/2

Dumb Money B

65. 10/6

The Royal Hotel B

66. 10/11

Strange Way of Life / The Human Voice B

67. 10/21

Killers of the Flower Moon B+

68. 10/22

My Love Affair with Marriage B+

69. 10/23

Beetlejuice B+ **

70. 10/26

Dicks: The Musical B

71. 11/2

What Happens Later B+

72. 11/3

Priscilla B-

73. 11/4

Anatomy of a Fall A

74. 11/5

Killers of the Flower Moon B+ (

2nd viewing)

75. 11/6

The Holdovers A

76. 11/8

Nyad B+ ****

77. 11/12

The Marvels B

78. 11/13

The Killer B+ *

79. 11/14

The Persian Version B-

80. 11/16

The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes B-

81. 11/17

Next Goal Wins B+

82. 11/25

Dream Scenario B

83. 11/26

Napoleon B-

84. 11/28

Saltburn B-

85. 12/2

Reinassance: A Film by Beyoncé B+

86. 12/4

May December A- *

87. 12/8

Eileen B-

88. 12/8

Leave the World Behind B *

89. 12/12

Godzilla Minus One B+

90. 12/14

Poor Things A-

91. 12/16

Fallen Leaves B

92. 12/20

Maestro A *

93. 12/21

Wonka B-

94. 12/23

The Iron Claw B

95. 12/31

Ferrari B

* Viewed streaming at home

** Re-issue (no new review)

*** SIFF Advanced screening

**** Viewed streaming in the Braeburn Condos theater

10. Barbie A-

10. Barbie A-

9. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse A-

9. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse A-

8. BlackBerry A-

8. BlackBerry A-

7. Past Lives A-

7. Past Lives A-

6. May December A-

6. May December A-

5. Close A

5. Close A

4. The Holdovers A

4. The Holdovers A

3. Anatomy of a Fall A

3. Anatomy of a Fall A

2. A Thousand and One A

2. A Thousand and One A

1. Maestro A

1. Maestro A

5. Babylon C

5. Babylon C

4. Saint Omer C

4. Saint Omer C

3. The Origin of Evil C

3. The Origin of Evil C

2. The Flash C

2. The Flash C

1. Renfield C-

1. Renfield C-