A DIFFERENT MAN

Directing: B+

Acting: B+

Writing: B+

Cinematography: B-

Editing: B+

A Different Man is a great companion piece to The Substance, and would make an incredible, deeply provocative double feature. Both examine vanity and beauty; both get deeply meta; both veer into body horror—but in very different ways, on all counts. There is less of the body horror element in A Different Man, but it is still definitively there: a disfigured man is given a procedure to give him a “normal” face, but instead of it slowly altering his face, the disfigured folds and mounds of skin peel off in fleshy pieces. This stuff gets far less screen time in A Different Man, but it was still gross enough that I had to look away from the screen.

The Substance gets much more into misogyny and celebrity, neither of which play a big part in A Different Man, which more specifically gets into the fine line between grotesquerie and exceptionalism. That said, much in the same way Demi Moore was cast in The Substance as an older actress giving into expectations of youthfulness, A Different Man casts the physically singular actor Adam Pearson, who has neurofibromatosis type 1 (a genetic condition that causes benign tumors to grow along the nerves), as an aspiring actor with a significant facial disfigurement.

In Pearson’s case, notably, his character, Edward, is given even more lumps and bumps all over his face than Pearson actually has. We follow Edward through roughly the first half of the movie, during which time it can be difficult to decide what to make of it. He meets his neighbor, Ingrid (Norwegian actor Renate Reinsve, previously seen in the 2022 film The Worst Person in the World), a young woman who takes an unashamed liking to him, something almost like a crush. This creates a fascinating dynamic, because she never directly addresses Edward’s condition. They get to know each other, both visiting his apartment and going out for pizza, and she doesn’t seem to notice all the people passing outside the window who turn to look at him. This only changes when a random guy knocks on the window and smiles and waves at him, which Ingrid finds strange but Edward says happens to him all the time.

And then, we learn that Ingrid is a playwright, humble at first but successful later, and she writes a play about her relationship with Edward, and the play she writes is all about how his condition plays into it. We’ll get back to that in a minute.

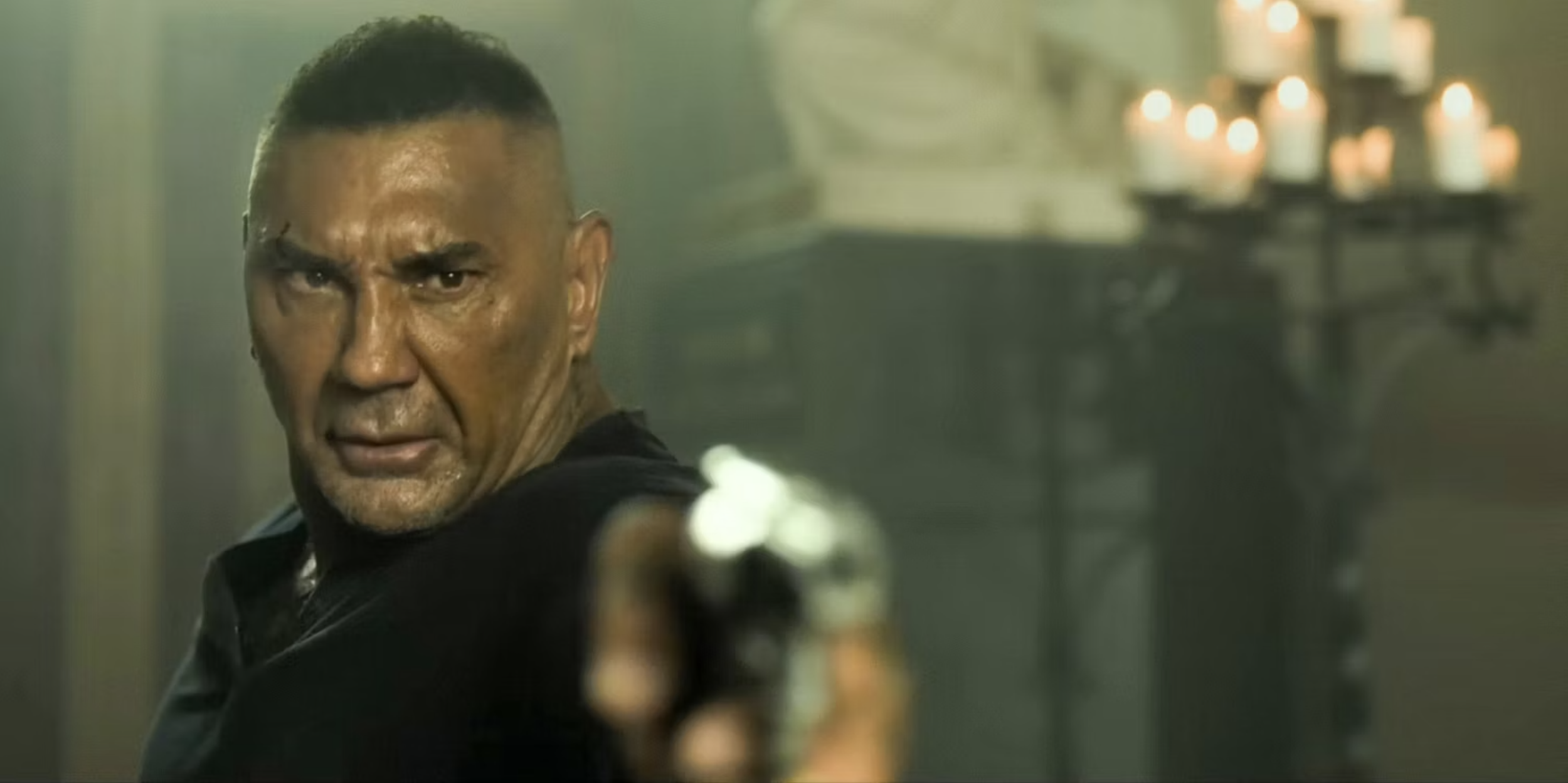

Because that all happens in the second half of the film, after Edward undergoes his procedure, and eventually pulls his face off, and is transformed into not so much a gorgeous man as just a regular, middle-aged guy—played by Sebastian Stan (best known as Buckey Barnes in the Marvel Cinematic Universe). Writer-director Aaron Schimberg never makes it explicitly clear why Edward, post-procedure, makes this pivotal choice: he isn’t honest about who he is with anyone, not Ingrid, not even the doctor who performed the procedure and shows up at his apartment not recognizing him. Edward, as played by Sebastian Stan, just assumes a new identity on the spot: Guy Moratz (in keeping with the meta threads of this film, someone later tells him that name “sounds made up”).

It was after this turn that I became more sure of how I felt about A Different Man, and I became more impressed with it. I’m not crazy about Adam Pearson’s performance as Edward, pre-procedure. He has a lot of mannerisms, the way he puts his hand on his hip or shrugs with a hand wave, that feel unnatural—like it’s someone you can tell is acting. Then it comes clear how intentional these mannerisms are, because once Sebastian Stan takes over the role, he mimics them impeccably. Edward remains the same deeply insecure man he always was, even when he suddenly looks “normal.” Ingrid, whom Guy meets after he crashes the auditions for her play, starts to get to know him, and more than once she calls him “jumpy.” You’d think she would recognize how his vibe reminds her of Edward, but maybe not; people can be blind to a lot when context changes.

Guy, who finds himself missing the exceptionality of life with his disfigurement, lands a part in the play. This is where the meta stuff really starts to fold over on itself: a cast had been made of Edward’s disfigured face for the procedure, which Guy then brings to wear when playing the part of Edward in the play. And as if that weren’t enough, another random person walks in during rehearsals, and it’s a man with the exact same condition—played, again, by Adam Pearson.

This guy’s name is Oswald. He’s played by a “realer” version of Pearson, still with the same striking facial features but without all the extra lumps and bumps we saw on Edward. Also: he’s British. Pearson himself is British, in fact: this is only his third feature film role (he’s also been in eight different TV shows, ranging from documentary to reality to narrative), his first in the 2013 science fiction thriller mood piece Under the Skin, a UK production. This means Pearson does accent work in A Different Man, which is completely convincing.

And Oswald could not be more different from Edward. He’s totally sure of himself, comfortable in his own skin, moves through the world as though his condition is entirely incidental. But Ingrid’s obsession with the use of this condition in her art gradually pulls Oswald into the production of the play, and one of the more amusing parts of A Different Man is now Oswald may be comfortable with himself, but he’s all for high-minded discussions of how he—and his condition—is used in art. Schimberg seems less concerned with moralizing about how we treat people who are different (or to some, even scary looking) than with examining how art stretches the lines of authenticity when incorporating real-life elements. This is ultimately what makes A Different Man work.

Schimberg is working on multiple planes here, with a script that is somewhat reminiscent of the work of Charlie Kaufman. I think perhaps he is a slightly better writer than director, and it would be fascinating to see a script he wrote directed by someone else. I found myself a little closed off from A Different Man during its first half, a bit skeptical of its performances, but then it took multiple turns that really won me over. Watch this movie with someone you can have a long conversation with about it afterwards, which is one of the greatest joys of the communal experience of cinema.

Both the same and different: the man, the men.

Overall: B+