WONKA

Directing: B-

Acting: B

Writing: C+

Cinematography: B+

Editing: B-

Special Effects: C+

Music: B-

An argument has been made that, well, Wonka is for kids, and kids deserve movies too, right? Well, here’ s my counter-argument: the likelihood that kids will indeed enjoy Wonka notwithstanding, there are still kids’ movies out there that are actually good. This is not one of them.

Mind you, it’s not terrible either. But that’s just the thing: there is a Roald Dahl legacy to live up to here, as well as a Gene Wilder legacy, and Wonka falls short on both counts. This movie doesn’t even live up to the 2005 Tim Burton film Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which I still insist was wonderful, I don’t care how many haters there are out there. Of course, that’s not to say any of these films have held up to the truly classic, enduring 1971 film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory—which, astonishingly, was rated G—but, on the flip side, kids today are neither likely to know anything about that film, nor have much interest in watching it if they do. It would be the equivalent of me having any interest in a film released in 1934 when I was ten years old.

The bummer of it right now is, if you want to take your kids to the movies, Wonka is nearly the only option. The only others in multiplexes right now are the animated films Migration and Wish, which are both getting worse responses than Wonka. Wonka, at the very least, is sprinkled with several genuinely charming moments, of the sort that are a signature of director Paul King. (King directed both of the Paddington films, and both of them are far superior to this.) If you’re one of the adults taking kids to this film, well, you’re kind of shit out of luck.

And, to be fair, it’s not just that it doesn’t live up to Roald Dah’s cinematic legacy. From the opening scenes, in which Timothée Chalamet dances with a bunch of people holding “Wonka” umbrellas behind him, the choreography middling and the lyrics unmemorable, I thought: Oh. This isn’t going to be great. The sequence ends with Wonka getting charged a fee for daydreaming, a brief gag that works better than any of the extended theatrics that came before it.

My biggest issue with Wonka is the visual effects. This movie was made on a budget of $125 million, and I just have to wonder: where the hell was the money spent? Just on the talent? Chalamet’s $9 million paycheck is objectively ridiclous, and yet even that is but a fraction of that budget. Once again, the shockingly good Godzilla Minus One comes to mind—that film was made for $15 million, and it looks far better than this.

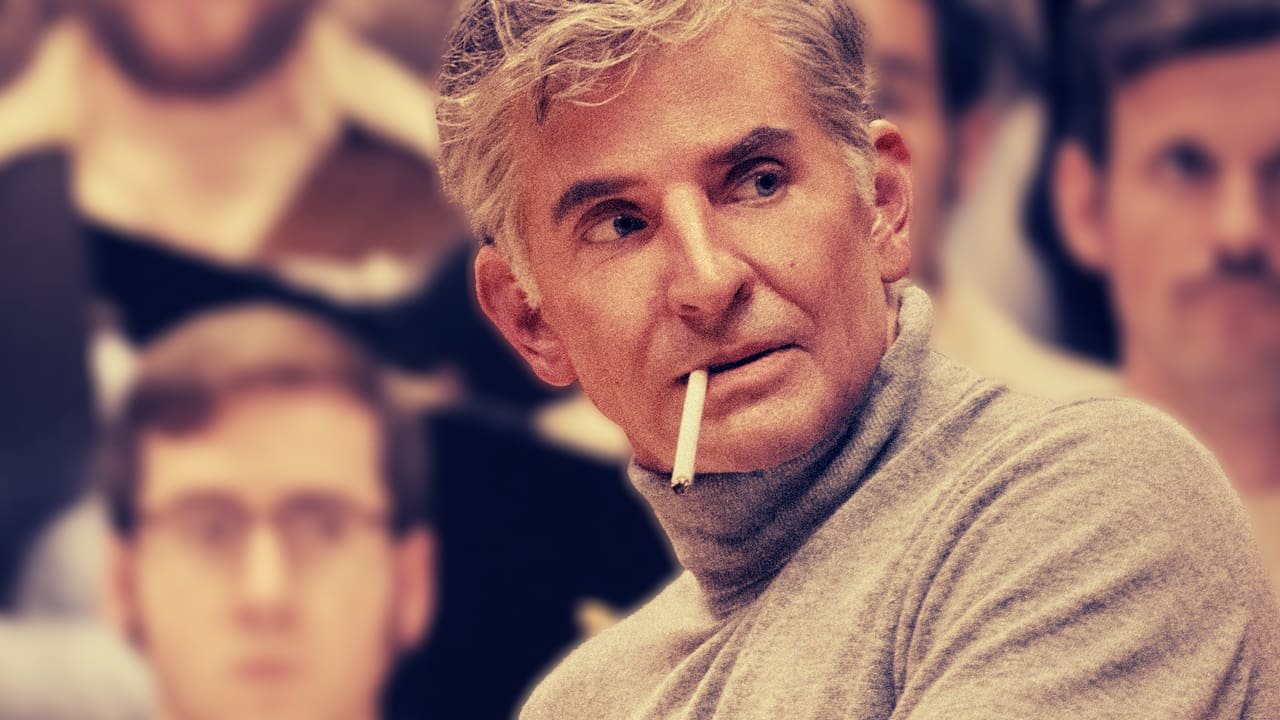

Wonka is appropriately color saturated for a film that is clearly presented as a musical fantasia. And yet, a huge amount of it is rendered in subpar CGI, giving it a far more artificial look than films about the same character released 52 and 18 years ago. I was especially mystified by the one Oompa Loompa, whose movements are noticeably jerky-jerky. How can a film this expensive to make look so bad? To give credit where credit is due, Hugh Grant imbues the Oompa Loompa with more personality than any single other character in the film, which almost makes up for the bad visual effects. Almost. (Side note: it’s also in this film’s favor that the Oompa Loompa is given full autonomy, and never becomes the stand-in for slave labor that the Oompa Loompas were in either of the previous films.)

To be fair, Timothée Chalamet, an objectively great actor, does his best with what he has to work with. As do a bevy of other big names who make up the supporting cast: Olivia Colman as Mrs. Scrubitt, the innkeeper who tricks Wonka into indentured servitude; Keegan-Michael Key as the Chief of Police, so easily bribed by Wonka’s rival chocolatiers with chocolate that he gains a ton of weight over the course of the film (and I find the idea that this is “fat shaming” to be debatable at best); Rowan Atkinson as Father Julius, also easily bribed with chocolate; Jim Carter as Abacus Crunch, one of the other indentured servants slaving away in the inn basement; even Sally Hawkins, the mom in the Paddington movies and here playing Wonka’s mother in a few flashback sequences. In none of these cases does the actor get as much to chew on as they deserve, in spite of Olivia Colman’s extensive screen time as one of many villains, but the one who most directly steals Wonka’s luck away from him.

Fundamentally, Paul King seems to have missed the point entirely, of Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which is about a possibly-corrupt, borderline sociopathic chocolatier weeding out the one good little kid in a group of spoiled brats. The only way Wonka’s return to that character’s story, particularly as a prequel, would make sense would be for Willy to learn the same kind of lesson himself as a youngster. Instead, Wonka is presented as pure hearted, and constantly taken advantage of by the adults around him who are the spoiled brats.

There is only one genuine kid in this movie, Calah Lane, who plays Noodle, also toiling away indefinitely in the inn basement. Lane is quite lovely, actually, one of the best things about Wonka, with onscreen charisma that helps keeps the proceedings watchable. But Noodle and Willy are both similarly pure of heart, dealing with heightened, standard kids-movie villains. Willy Wonka is supposed to be backed with subtext, and Wonka, generally pleasant as it is to watch, is all text.

All of that brings us back to this: kids will have a great time. The group of kids in the row of seats behind me, who did not shut the fuck up the entire film, certainly did. Surely they neither know nor care anything about Gene Wilder’s or even Johnny Depp’s iterations of Willy Wonka. For them, there is only Timothée Chalamet. But here’s the key difference: none of those kids are going to grow up regarding this as an unfortgettable classic from their childhoods. It’s just another passable outing at the movies, and in the context of its cinematic legacy, that’s a real shame.

Hugh Grant’s ample charms can’t elevate a middling achievement.

Overall: B-